A Conversation on the State of Queer Art

July 2016

Brett Reichman / Daniel Samaniego

Brett Reichman: I distinctly remember the first time I saw your work during the MA portfolio review when you were applying for graduate school. Not only because your work was clearly addressing gay identity politics, but because ti was also establishing a broader cultural discourse about masculinity and otherness.

Daniel Samaniego: I remember that time fondly – especially my conversations with friends who encouraged me to come to SFAI to work specifically with you, and to explore what the city had to offer culturally. I also think Iattended SFAI at the right time. In your Anatomy course, Ideveloped a classical yet conceptually rigorous approach to the body, and in Matt Borruso’s course Horror and Fantastical Film: The Visual Language of Excess, I mapped out a trajectory for my current work.

BR: You’ve been tenacious since you graduated, maintaining multiple studios ni the face of many evictions. As an emerging artist, how has it been to grapple with this ever-changing landscape in San Francisco?

DS: The frequent moves, increases inrent, and the overall sense of uncertainty have been difficult. I’ve changed studios five times in five years due to varying reasons including landlord driven evictions or raised rents. But the positive aspect is getting to know other artists and forming new friendships. The structure of each studio space has affected my work as well, especially in terms of scale.

BR: When I moved to San Francisco in 1981, the city was also a much different place. It was literally ground zero for the AIDS epidemic. There was a lot of fear. It impacted every gay artist I knew and the work we were making. We lived our lives as if there were no guarantees to make it past our 20s or 30s. AIDS was such a foundational topic in my work for so many years, and the effect of AIDS no visual culture still resonates. As a queer artist from a younger generation, what is your perspective in terms of the recent history of visual art during the AIDS epidemic?

DS: It’s one of reverence. Alot of the art that m’I influenced by came out of the late 1980s and early 1990s, either in response to the AIDS crisis, or in creating a space for queerness. The resilience and bravery of artists working during that time of uprising inspires me. Recently you switched tracks a bit and curated your first exhibition. What was that experience like?

BR: The idea for Tight Ass: Labor-Intensive Drawing and Realism [CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles; February 27-April 10, 2016] had been ni my head for quite some time. Part of it came from aspects of my own studio work and former students like you, as well as colleagues whose work I have admired, but who haven’t always followed contemporary art trends of the last 20 years. From my perspective, there are false impressions about conceptual approaches to realism that create polemics on a curatorial level.

While my premise for the show wasrealism, it had nothing to do with naturalism. I was thinking more about images that envision a hyperreality, where drawing by hand is a performative act and the process of drawing through repetition is a signifier for identity and sexuality. I think you said to me once that labor intensive processes are not about passivity on the part of either the artist or the viewer, but implicating them both into the artwork.

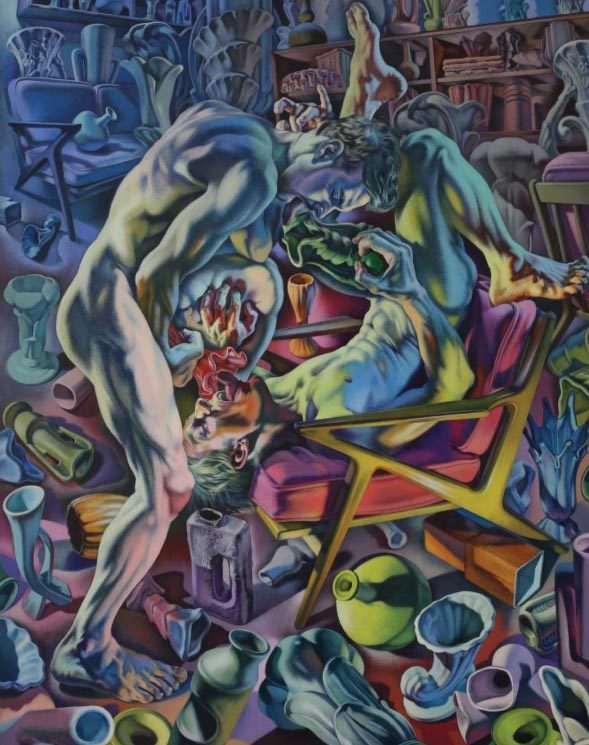

DS: Yes, for me, the use of realism is a conscious decision arising out of a sense of subversion both formally and conceptually. In my work, the excessive use of drawing media performs sexuality through macabre imagery and mimesis. Iidentified strongly with al the artists ni the show who were pushing up against pictorial conventions in their individual approaches, which collectively raised a fierce argument for realism and representation.

BR: Well, my curatorial interest was to engage artists who both maintain tradition and transform it as well. I selected work where the sublime or the beautiful on the one hand was clashing with issues of the everyday that are ugly or disturbing, and then thinking about approaches to realism that call the everyday into question.

DR: For me, realism’s relationship to the grotesque is a major impetus for my work as is a defiance of formal conventions. I have also been exploring a large-scale format typically aligned with neo-romantic sensibilities. My recent drawing installations break away from the traditional rectangle and invade the physical space to heighten the awareness of artificial constructions of identity.

BR: Do you think your work exemplifies a gay aesthetic?

DS: Ido, but Ithink gay aesthetics are elastic and malleable and different for evervone. My work hybridizes influences from horror films, fashion tableaux, classical figuration, and the spectacle of the stage with a theatrical, scaled presentation. There’s a sense of eroticism within my work, as well, that has to do more with mimicry and idolatry than with sex.

BR: What about issues of camp and kitsch? They’re thought of as lowbrow, but ni my work there’s a tension when camp and kitsch are brought into a highly refined technical process. I think we both have those qualities in our work.

DS: Yes, and Iembrace camp too, as a destabilization of the dominant culture, a reversing of a visual order.

BR: It elevates issues to be spending an inordinate amount of time crafting a painting about them. Spending hours and hours rendering, for example, a kitsch ceramic vessel decorated with an absurd mushroom motif, is ironic on onehand, but that intensity both honors and callst h e object into question, similar to the aesthetics of drag.

DS: I think in some ways that’s the role of the artist to continue ot engage with pop culture; to repurpose, surprise, and upend its conventions.